Decoding Market Jargon: Common Terms Every Investor Should Understand

Financial markets have a language all their own.

Sometimes it feels like a secret code — a way for insiders to speak in symbols that outsiders mistake for magic. But beneath that language lies structure, logic, and human behaviour. Learning the words is the first step toward seeing the system clearly.

Let’s decode some of the most common and misunderstood terms in the world of trading and investing.

Assets and Markets

An asset is anything that holds or is expected to hold value — cash, stocks, bonds, real estate, even intellectual property. Assets form the foundation of every balance sheet: what you own versus what you owe.

The cash market (also called the spot market) is where assets are traded for immediate delivery. By contrast, derivatives or futures markets involve contracts whose settlement happens later. The difference between the two is time — and with it, speculation.

A commodity is a raw material or primary agricultural product — oil, wheat, gold — that is interchangeable with others of its kind. Commodities often move differently from financial assets, providing a hedge against inflation and currency risk.

Emerging markets refer to developing economies that are growing rapidly but still lack the stability of mature financial systems. They offer high potential returns, but with higher volatility and political risk.

Stocks and Ownership

A common stock represents ownership in a company. When you hold it, you own a piece of its assets, earnings, and future potential. In return, you may receive dividends — regular cash payments from the company’s profits — and the possibility of capital gains when the stock’s price rises.

The dividend yield tells you how much a company pays out in dividends relative to its stock price. For example, if a £100 share pays a £5 annual dividend, its yield is 5%. High yields can signal value — or distress, if prices fell too far.

A blue-chip stock is the opposite of speculative. These are shares in established, financially stable corporations — the giants of their industries. They rarely grow fast, but they rarely collapse either. Investors hold them for reliability, not excitement.

An IPO (Initial Public Offering) is when a private company sells its shares to the public for the first time. It marks a transition from internal funding to market-driven ownership — from private story to public scrutiny.

Bonds and Debt

A bond is a loan, not an ownership stake. When you buy one, you lend money to a company or government in exchange for interest payments and the promise of repayment at maturity. Bonds trade on expectations of creditworthiness — a reflection of trust.

The default rate measures how often borrowers fail to meet those obligations. Rising default rates often signal stress in the economy or excessive leverage beneath the surface.

Cash flow — the movement of money in and out — underlies both corporate health and sovereign solvency. Profit on paper means little if cash cannot move freely.

Measuring Returns

An annual return expresses how much an investment’s value changed over one year, as a percentage. It’s the simplest measure of performance, yet it hides the path taken — a 10% return could come from steady growth or wild swings.

A capital gain is the profit made when you sell an asset for more than you paid. It’s realized value — the difference between potential and actual.

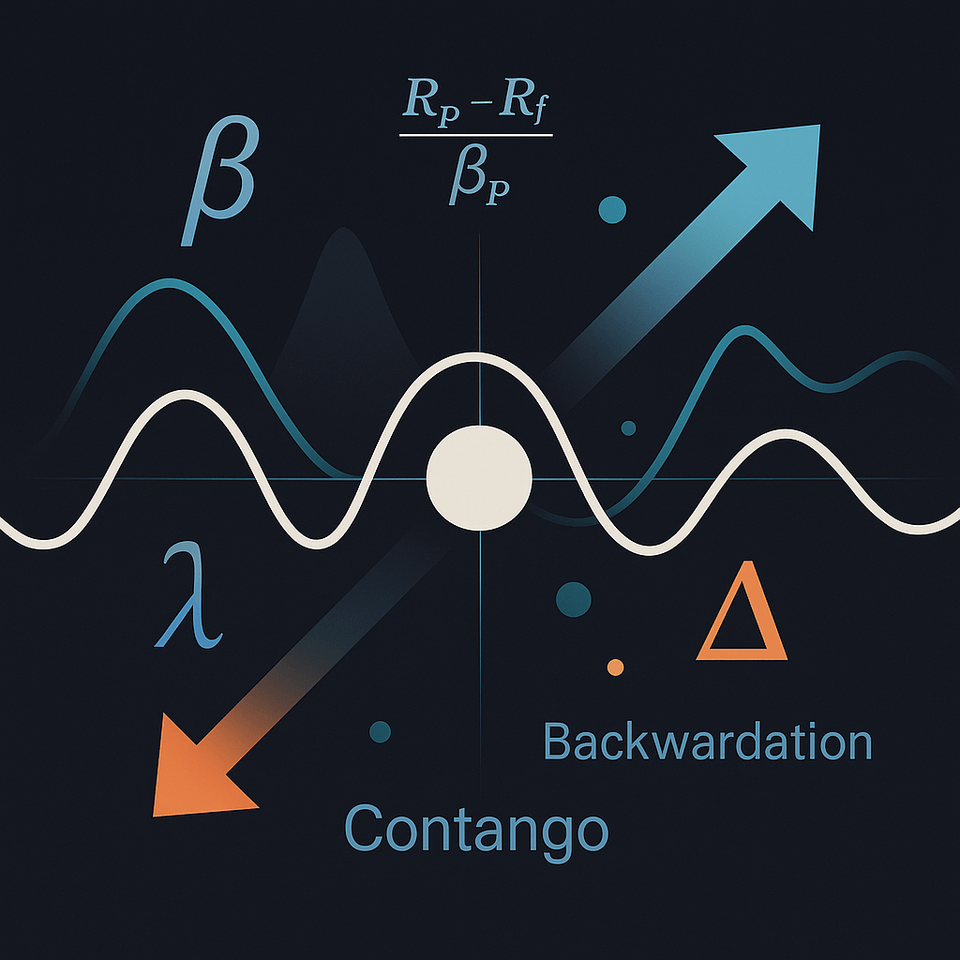

The Treynor ratio refines this by measuring return per unit of systematic risk:

where

It tells us how efficiently a portfolio converts market exposure into reward.

Understanding Risk

Beta is a measure of how much an asset moves relative to the overall market.

A beta of 1 means it moves in sync; above 1 amplifies swings; below 1 dampens them.

It quantifies sensitivity to the crowd.

Alpha, by contrast, is performance beyond what beta predicts — the elusive “edge.” It represents skill, timing, or inefficiency captured before the market adjusts.

Volatility measures how much prices fluctuate — mathematically, the standard deviation of returns. Yet beneath the formula lies emotion: volatility is fear and greed given numerical form.

Leverage magnifies both gains and losses. Borrowed capital can accelerate growth, but also collapse. Used wisely, it multiplies opportunity; used carelessly, it erases it.

The Greeks and Derivatives

A derivative is a financial contract whose value derives from an underlying asset — such as a stock, commodity, or index. Options and futures are the most common types.

Option traders speak in “Greeks,” which describe how sensitive an option’s price is to various factors:

- Delta (

- Gamma (

- Theta (

- Vega (

Together, they form a language of control — a way to measure what can’t be known with certainty.

Futures, Curves, and Market Structure

In futures markets, two peculiar words describe the shape of expectations: contango and backwardation.

- Contango: When future prices are higher than today’s — often due to storage costs or expectations of rising demand.

- Backwardation: When future prices are lower than today’s — reflecting scarcity or urgency in the present.

These curves are more than pricing quirks; they reveal psychology. Contango reflects comfort and abundance. Backwardation reflects tension and need.

Arbitrage lives in the space between such inefficiencies — buying low in one place and selling high in another. In theory, it’s “risk-free profit.” In practice, it’s a race of speed, precision, and liquidity.

Liquidity and Market Mechanics

Liquidity measures how easily an asset can be traded without drastically changing its price. High liquidity means tight spreads, deep order books, and stable prices. Low liquidity means fragility — a single trade can shift the market.

A spread is the difference between the bid and the ask:

- Bid: The highest price a buyer is willing to pay.

- Ask (or offer): The lowest price a seller will accept.

That small gap between them — often a few cents — is where market makers live. It’s the toll of immediacy, the cost of entering or exiting a position right now.

Market Cycles and Psychology

A bull market is a period of rising prices and optimism. Investors believe in growth; confidence feeds itself.

A bear market is the opposite — falling prices, pessimism, retreat.

Both are as much emotional climates as financial ones.

Contagion describes what happens when panic spreads — when one market’s collapse infects another through debt, leverage, or fear. Financial history is a chain of contagions, from 1929 to 2008 to the crises yet to come.

Inflation is another kind of contagion — a slow erosion of purchasing power. It eats at savings, distorts incentives, and redefines value. Markets respond by repricing everything: labour, capital, and hope.

Portfolios and Funds

An ETF (Exchange-Traded Fund) pools together many securities and trades like a stock. It gives investors diversified exposure to an index or sector without buying each asset individually.

ETFs embody the modern idea of passive investing — participating in the system rather than trying to outsmart it. Yet even here, the illusion of neutrality hides design: what’s included, weighted, or omitted still tells a story.

Bringing It Together

All these terms — from beta to backwardation, from dividends to derivatives — are fragments of a single language. A language built to describe how humans assign value, manage risk, and navigate uncertainty.

Understanding them does more than improve your financial literacy. It cultivates discernment: the ability to see through complexity to the structures beneath.

If you enjoyed this post, explore the Understanding Market Mechanics series for deeper dives into liquidity, reflexivity, and the architecture of markets.