Hacking, Exploits, and the Hidden Bazaar of Power

The hacker we imagine and the world we inhabit rarely match.

We are sold the myth of the lone teenager in a hoodie, hunched over a glowing screen, breaking into systems either for mischief or petty profit. On the other side of the story stand governments, intelligence agencies, and security companies—polished, well-funded institutions wearing the mantle of “protectors.” This split keeps the narrative tidy. There are the criminals, and there are the guardians, and the rest of us are passive bystanders hoping the latter keeps the former at bay.

But if you follow the money, that story collapses quickly.

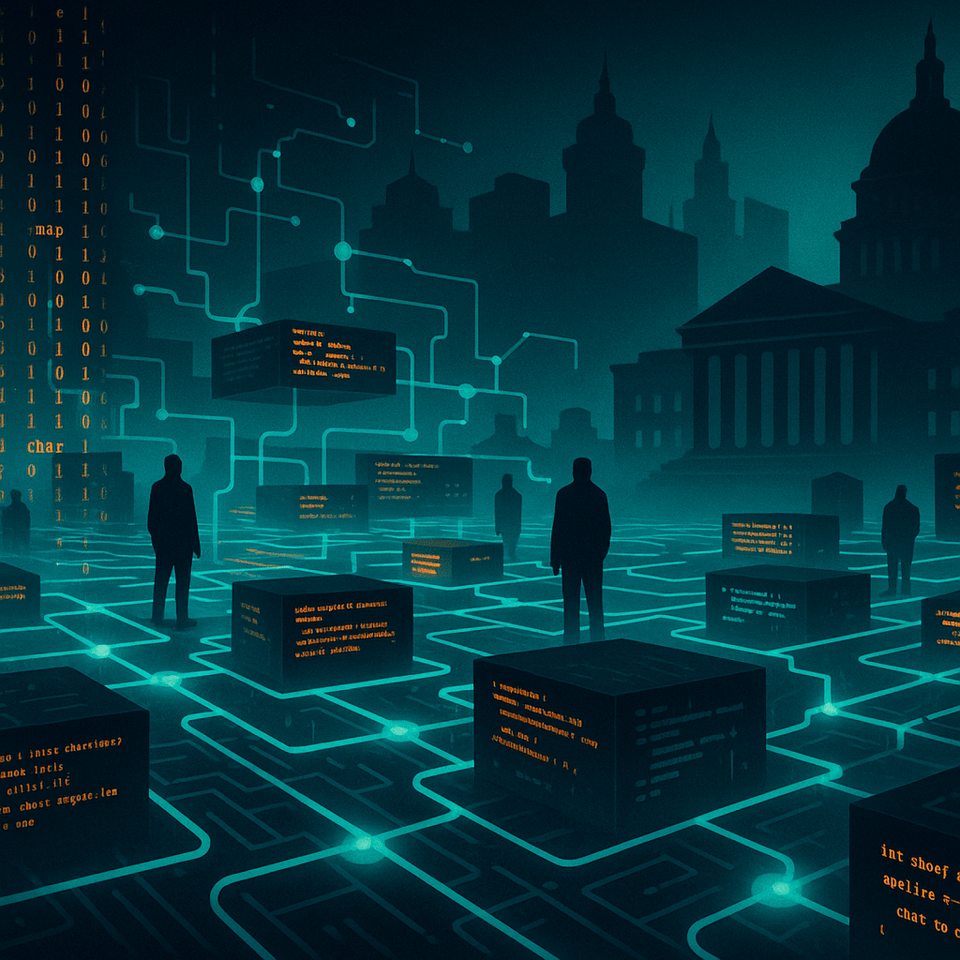

Beneath the surface of our networks lies a market. In this market, the commodities are not wheat, oil, or steel, but vulnerabilities, access and silence. Exploits are discovered, refined, packaged and sold. Access to corporate networks trades hands. Entire populations become targets, not because of personal guilt, but because their devices sit on a vulnerable architecture. And in this market, the largest, most consistent purchases are almost never made by kids in hoodies. They are made by governments, intelligence institutions and the very security companies that publicly claim to protect us.

This tension—between the public story and the private market—is where hacking stops being a thriller trope and becomes a structural feature of how modern power operates.

From Curiosity to Commodity

For many, hacking begins in innocence. It starts with curiosity, not malice. Someone notices that a login form behaves strangely when given odd input, or that a protocol specification leaves a gap between what is formally described and what real-world implementations actually enforce. A weird error message appears, a system responds in a way it “shouldn’t,” a constraint that seemed absolute turns out to be surprisingly flexible. This is how most vulnerabilities are first glimpsed: as cracks in a facade that was sold to us as solid.

At that moment, there is a fork in the road. One path leads to disclosure, where the person who found the flaw contacts the company or institution responsible, files a report, and ideally receives recognition or a bug bounty. The system is patched, users are safer and the exploit dies young. It is an orderly story: discovery, disclosure, fix.

The other path leads into the market.

A previously unknown vulnerability, a so-called “zero-day,” is not just a bug; it is an instrument of leverage. If no one else knows about it, that single flaw can open doors into millions of devices or dozens of supposedly secure networks. It can be used to read messages people thought were private, to move across corporate infrastructure silently, to sabotage machinery or siphon data without raising alarms. The value of that vulnerability is directly tied to three things: how many systems it affects, how quietly it can be used and how few people know it exists.

This is where curiosity turns into commodity. Exploits get wrapped in code, documented, given interfaces that allow less skilled operators to deploy them. Access to compromised systems is catalogued and tagged. Data stolen through one breach is packaged and resold through another channel. The technical brilliance that discovered the vulnerability becomes just one layer in a chain of monetisation, coordination and control.

We often frame this as “cybercrime,” and at the low end that is true: there are plenty of actors whose main aim is ransom, theft or disruption. But alongside and above them, there is a quieter, far better funded set of buyers. These buyers are not smashing and grabbing. They are collecting and curating.

The Quiet Customers of the Shadow Bazaar

Once you accept that vulnerabilities are assets, the obvious question becomes: who can afford the best ones?

The answer is rarely comfortable. The most expensive, most potent exploits do not primarily circulate among small-time criminals. They are bought by states. Intelligence agencies acquire them to infiltrate foreign governments, corporations, activist networks and infrastructure operators. Law enforcement units purchase tailored tools that promise access to phones, laptops and messaging apps, framed as necessary to combat terrorism and organised crime. Large security companies sit between these institutions and the raw exploit developers, packaging capabilities into polished platforms labelled “lawful intercept,” “offensive security” or “remote endpoint solutions.”

Much of this trade never touches the stereotypical “dark web” markets that headline writers like to invoke. The highest-grade exploits are often exchanged through private broker networks, closed circles or through companies that present themselves as entirely legitimate vendors. Contracts are signed, NDAs are enforced, compliance documents are drafted. Yet beneath that corporate veneer, the core transaction is simple: pay for secret vulnerabilities, pay for persistent access, pay for the ability to reach into systems that the rest of the world believes are secure.

The more public dark web markets, filled with stolen credentials, lower-tier malware and recycled exploits, act like a noisy intersection more than a secluded lair. Criminal groups, freelance developers, data brokers and opportunistic buyers meet there, trade there and learn from one another. Governments and intelligence institutions do not need to send agents into random Tor forums to shop in person. They outsource that work to intermediaries, to contractors, to “research teams” with sufficient deniability built into their operations. Still, the ecosystem is linked. Techniques pioneered in state labs leak into criminal hands. Tools originally designed for “lawful” use find their way into repressive regimes or get repurposed by actors beyond the original supply chain.

In theory, states justify this posture as necessary. Having access to exploits and offensive tools is framed as essential to national security, counterterrorism, and serious crime investigations. In practice, that justification often comes at the cost of everyone else’s safety. When a government chooses to hoard a vulnerability instead of disclosing it, it makes a bet: that it can maintain control over who uses that exploit, that adversaries will not independently discover it and that the benefit of having the weapon outweighs the systemic risk. It is a bet placed on behalf of millions of people who have no idea the wager was made.

Insecurity as a Resource

The deepest problem in this entire ecosystem is not a single exploit, tool or company. It is the way insecurity itself becomes a resource—something to be farmed, priced and selectively distributed.

If a phone’s operating system were perfectly hardened, breaking into it would be nearly impossible even for powerful states. If a messaging platform were unbreakably secure, traffic flowing through it would be out of reach. If critical infrastructure were genuinely resilient and segmented, compromise would be much harder to use as leverage in geopolitical conflict. In a world where these things were true, the utility of hoarded exploits would drop dramatically.

Instead, we inhabit a world of managed vulnerability. Systems are locked down just enough to appear responsible, but not so much that they are opaque to powerful institutions. Governments maintain processes for deciding whether to disclose or retain vulnerabilities, but the criteria are rarely transparent. Security companies promote their defensive products loudly while quietly building and selling offensive capabilities to the highest bidders. The same engineers who could push for more robust default security often find themselves rewarded more for developing tools that bypass those protections.

When insecurity is treated as an asset, patching becomes a political choice rather than a purely technical one. An unpatched vulnerability is not simply an oversight; it might be a deliberate decision to leave a door open because someone important finds that door useful. From the perspective of everyday users—journalists, activists, business owners, families—this means that their exposure is sometimes a side effect of strategies that were never explained to them, adopted in rooms they will never enter, justified by documents they are not allowed to read.

The collateral damage is not theoretical. Ransomware attacks against hospitals, access to dissidents’ phones using commercial spyware, breaches of sensitive corporate data that cascade down to ordinary people—all of these lean on the same underlying reality. Once you normalise a marketplace where the most powerful customers are those with the greatest interest in keeping exploits alive, you normalise a world where your safety is secondary to someone else’s operational convenience.

None of this means that all state use of hacking tools is inherently illegitimate, nor that all security companies involved in offensive research are acting in bad faith. It does mean that the simple moral story we are often told—of heroic institutions battling chaotic criminals—is no longer adequate. The dark web, the exploit market, the shadowy bazaar of access and control: these are not external to our systems of power. They are woven into them.

Facing that truth is uncomfortable, but necessary. So long as we treat hacking as a fringe activity and exploits as freak accidents, we will continue to misunderstand the landscape we actually inhabit. The real question is not whether the dark web exists or whether hackers are out there somewhere. The real question is what it means when governments, intelligence institutions and security companies are among the most important customers in a marketplace built on the sustained insecurity of the systems we rely on every day.