The Prime Effect

Somewhere in the last two decades, profitability stopped living inside the product and moved into the system around it. A cheap hot dog, a “free shipping” badge, a suspiciously generous promo—these aren’t quirks. They’re architecture.

I call it the Prime Effect: businesses deliberately take losses at the front door to win a long-term default relationship, then earn it back across an ecosystem over time—through frequency, habit, and a portfolio of internal economics. The mechanism is simple: subsidise adoption, compound habit, recover margin elsewhere. In the 90s you won by selling a profitable thing. Today you often win by making the easy choice feel inevitable.

What looks like “taking a hit” is often just a reallocation of where profit is allowed to exist. The front door is priced for adoption, not margin. The back rooms are priced for recovery. And because modern businesses can measure behaviour in real time—conversion, retention, repeat rate, basket size—they can afford to treat early losses as investment, not failure.

That’s why loss leaders stopped being rare stunts and became operational doctrine. Some offerings are designed to be unprofitable on purpose, because their true job is to create a habit, establish trust, and build the kind of inertia that makes switching feel like friction. Once a company becomes your default, it doesn’t need to win you over every time. It just needs to stay close enough to be chosen automatically.

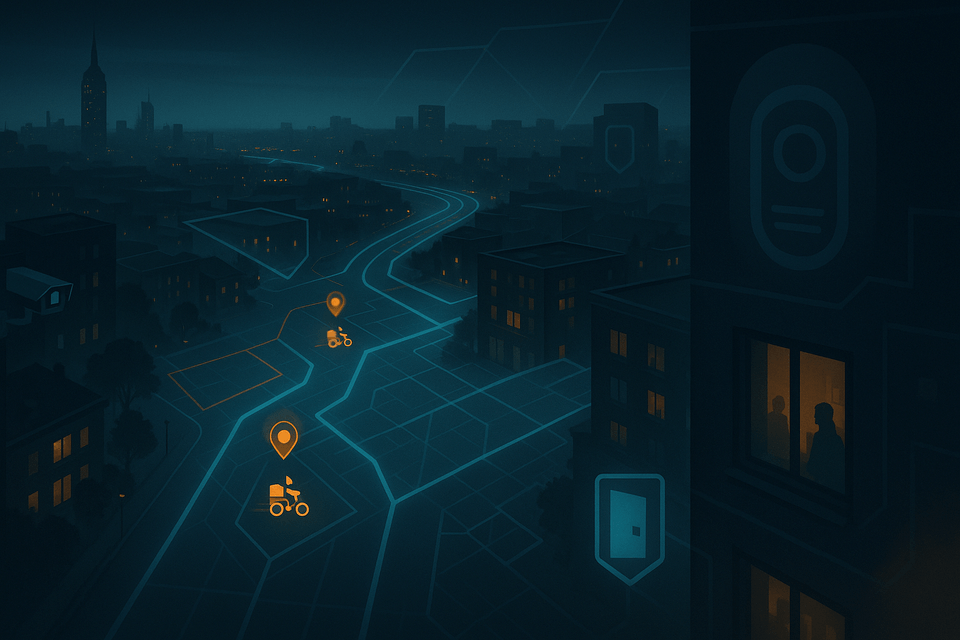

You can see it everywhere: Amazon subsidising consumer convenience through AWS profits, Costco using a hot dog as a promise, delivery platforms absorbing costs to keep both sides moving, venture-backed startups buying time until the loop tightens. Different industries—same underlying play: sacrifice margin at the entry point to control the relationship.

This isn’t just a story about business strategy. It’s a story about how consumer behaviour gets shaped—quietly, gradually, and at scale—until the system feels less like a choice and more like the water we swim in.

Modern Business Models vs. the 90s Model

In the 90s, many winning businesses were built like sturdy machines. You made a thing, you sold the thing, and the thing itself carried the burden of profitability. Distribution was scarcer and slower, shelf space and broadcast airtime mattered, price transparency was lower, switching costs were naturally higher, and marketing worked through broad strokes rather than microscopic targeting. In that world, it made sense to treat each product as a profit centre, because feedback loops were slower and because you couldn’t easily afford to run a large part of the business at a loss while hoping some other part made it back later. When loss leaders existed, they were usually bounded and local—an in-store tactic designed to pull you through aisles, not a core economic philosophy.

Today’s model has inverted the centre of gravity. The “thing” is often just the front door. Companies can shape behaviour with rapid feedback loops, personalise incentives, adjust pricing dynamically, and iterate on the customer journey like software. Instead of asking “does this product make margin,” modern businesses increasingly ask “does this interaction increase lifetime value.” They design for retention, habit, and default choice. They can afford to treat parts of the experience as intentionally unprofitable because the business isn’t one product anymore. It’s a portfolio, and the portfolio has internal economics: some components exist to generate cash, others exist to generate frequency, others exist to generate trust, and the best ones do all three at once.

Loss Leaders in the Age of Ecosystems

Loss leaders used to be items. Now they’re often experiences, services, and whole layers of convenience. The modern loss leader isn’t merely a cheap object that gets you into the store; it’s a hook that rewires your expectations. It trains you to think “this is where life is easiest,” and once your brain has accepted that, the rest of the ecosystem becomes less about comparison and more about momentum. This is what makes modern subsidy so powerful: it doesn’t only buy purchases, it buys habits, and habits are hard to dislodge because they move beneath conscious decision-making.

What makes this possible is cross-subsidy at scale. When one part of a company throws off high-margin profit, it can bankroll low-margin or negative-margin touchpoints that feel generous to the customer. That generosity isn’t fake; it’s just strategic. The business is effectively investing in the customer relationship, paying today to own tomorrow’s default choice. And because the modern company can see the data, it doesn’t have to subsidise everyone equally. It can subsidise selectively, surgically, targeting new users, high-value cohorts, specific geographies, specific times, and specific behaviours. The loss is no longer a blunt instrument. It’s a dial.

This is also why these models can feel almost like a magic trick when viewed from the outside. If you isolate a single order, a single trip, a single transaction, you can convince yourself the company has no idea what it’s doing. But the point is that the transaction is no longer the unit of success. The customer is. The system is.

Subscriptions and the New Business Contract

Subscriptions did not become popular because businesses suddenly discovered predictable revenue. They became popular because subscriptions reshape psychology. A subscription can turn consumption into identity. It changes the customer relationship from episodic to continuous, from “I bought something” to “I’m part of something.” That shift matters, because it reduces friction and increases inertia. Once you’re paying, you feel a subtle pressure to use what you’ve paid for. You stop asking “should I spend” and start asking “how do I get value from what I’m already spending.” The decision changes from purchase to justification, and justification is a far easier mental hill to roll down.

This is why Prime is more than “free shipping.” It’s a behavioural contract. It makes Amazon feel like the default store because the marginal cost of choosing Amazon feels lower, even when it isn’t. It bundles convenience into a single emotional word: membership. And bundling is the quiet genius of the subscription era, because when one payment unlocks multiple benefits, cancellation feels like losing many things at once, even if you only use a few. Subscriptions also allow businesses to smooth risk. They can plan inventory, content budgets, logistics, and growth with more confidence because they have a recurring baseline. That baseline becomes the runway from which experimentation and subsidised customer acquisition can safely launch.

But the subscription turn also contains its own shadow. When every company wants a recurring claim on your wallet, the customer begins to feel crowded. Subscription fatigue isn’t just annoyance; it’s a signal that the ecosystem is reaching saturation. And when growth slows, the temptation is to extract more from the same base: raise prices, add tiers, insert ads, reduce generosity, squeeze the parts that were once the hook. The subscription model is stability, but it is also a promise. If the promise breaks, loyalty flips into resentment.

The Playbook in the Wild

Amazon is the clearest expression of the modern portfolio model because it embodies the split between a profit engine and a habit engine. AWS is a high-margin machine that funds a sprawling consumer experience where convenience is constantly being refined and subsidised. That subsidy doesn’t only show up in pricing; it shows up in logistics density, speed expectations, returns policies, and the subtle sense that Amazon is the path of least resistance. When you combine that with Prime, you don’t just have a store. You have an operating system for consumption, where the point is not a single profitable transaction but a lifetime of default behaviour.

Costco, on the other hand, shows how trust can be engineered without feeling engineered. The hot dog is famous because it’s not merely cheap; it’s a symbol. It tells the customer that restraint is part of the culture, that membership is a relationship rather than a squeeze. Costco’s power is less about extracting margin from goods and more about creating a value environment people believe in. That belief turns into volume, and volume turns thin margins into meaningful profit. The hot dog works because it’s a credibility anchor. It’s proof that the deal is real, and proof is worth more than persuasion.

Uber Eats reveals a different kind of modern logic, the logic of marketplaces. Delivery platforms don’t just sell food delivery; they manage balance. They must keep enough drivers available that customers get good service, while keeping enough customers ordering that drivers keep earning. This balance is fragile, and fragility creates subsidy. A platform might pay more on a particular trip, offer promotions in a particular area, or absorb costs in a particular moment because the true objective is liquidity, reliability, and habit formation. It’s not that every order must be profitable; it’s that the marketplace must remain alive. Once it’s alive, revenue is captured through fees, scale, and increasingly through the monetisation of attention inside the app, where placement, visibility, and sponsored positioning become their own profit layer.

GoPuff, and the broader era of venture-subsidised growth, is what happens when the portfolio logic is funded externally before it’s funded internally. The early phase is an experiment in speed and habit: prove that people will change their behaviour if convenience is cheap enough and fast enough. Investment capital becomes the temporary profit engine, buying time until the company finds durable unit economics through density, operational efficiency, private label, fees, or new monetisation layers. When capital is abundant, this can feel like the future arriving early. When capital tightens, it reveals the underlying question the subsidy was postponing: can the habit survive without the discount.

The common thread across all of these examples is that modern business models have become architectural. They build corridors that guide behaviour, rooms that keep you comfortable, and doors that are easy to walk through but harder to walk back out of. The 90s taught companies to win by selling good products profitably. The present teaches companies to win by shaping environments where profitability emerges across time, across a system, across a relationship. And once you see that, the “irrational” losses start to look like something else entirely: not failure, but strategy—an investment in becoming your default.