Life at the Edge

We often speak about life as if it were a delicate ornament, something that survives only in a narrow corridor of acceptable conditions, as though existence itself were a luxury rented from a forgiving universe.

That intuition makes emotional sense because we are fragile in very specific ways, and our bodies carry hard limits that feel like the limits of reality itself; we burn, we freeze, we sicken, and we break. Yet biology, observed patiently and without sentimentality, keeps offering a different story, one in which life is less a porcelain object and more a living negotiation, constantly re-drafting its terms with whatever environment it inherits, whether that environment is fertile soil, irradiated concrete, or oceans that boil and freeze in different corners of the planet.

When you look closely, resilience in nature rarely resembles heroism, and it almost never resembles purity, because life does not survive by staying untouched; it survives by becoming appropriate. It finds gradients, it finds niches, it finds loopholes in the physics of scarcity, and then it turns those loopholes into homes. The result is not a comforting tale in which nature “wins,” but a more unsettling and more beautiful truth: the boundary between “habitable” and “uninhabitable” is not as stable as we imagine, because living systems keep learning how to make a living where we assumed no livelihood was possible.

What follows are three thresholds—radiation, plastic, and temperature—where our instincts insist life should fail, and where life, in its quiet and unsentimental way, demonstrates that “should” is not a biological category.

The Dark Fungi of Chernobyl

Chernobyl endures in the human imagination as a symbol of invisible harm, not simply because radiation is dangerous, but because it is danger without a face, danger that lingers in dust and walls and time, and danger that makes the ordinary world feel suddenly untrustworthy. In that kind of landscape, we naturally expect a vacuum of life, a sterile zone where the story ends, and in many ways it did end for countless organisms that could not adapt to the abrupt violence of contamination.

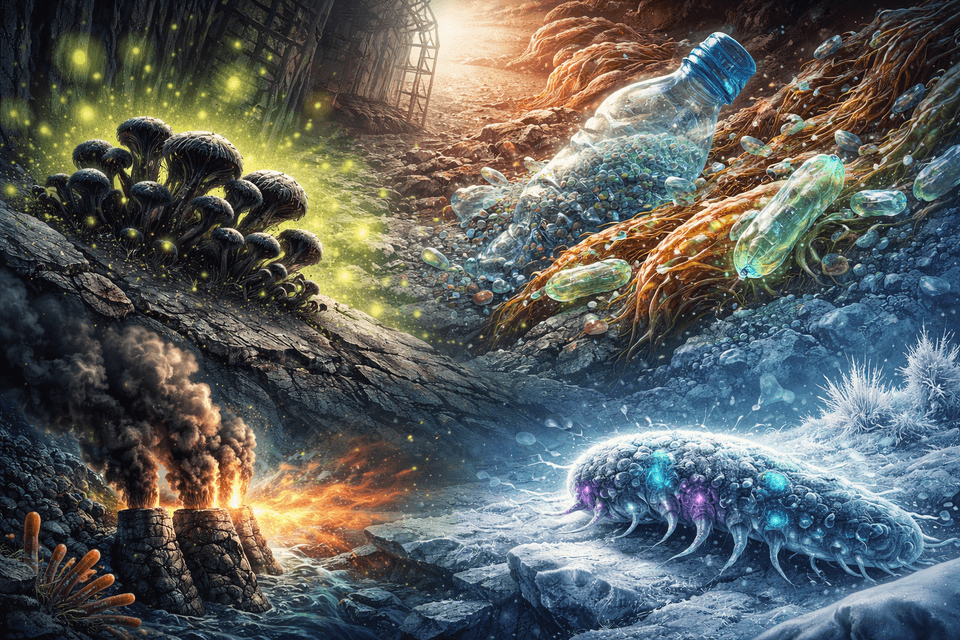

Yet researchers have repeatedly documented fungi—often melanized, meaning heavily pigmented with melanin—persisting in and around highly irradiated environments associated with the Chernobyl site, including observations that some fungi appeared to grow toward sources of radiation rather than away from them. This is not the fantasy of an organism “enjoying” radiation in a human sense, but it is a reminder that what we experience as poison can, under certain biological architectures, become a signal, a stressor to be managed, and possibly even an energy landscape to be exploited.

The fascination deepens when you move from observation to mechanism, because melanin seems to be more than a passive shield that merely blocks damage, and there is scientific discussion around how ionizing radiation can alter melanin’s electronic properties in ways that correlate with increased growth in melanized microorganisms under experimental conditions. That claim should be held with care, because the phrase “radiation-eating” invites a cartoonish interpretation that the science does not require, and because the boundary between “benefit,” “tolerance,” and “correlation” can be easy to blur when a story is emotionally magnetic.

Still, even the cautious version carries philosophical weight: melanin may function as a kind of interface, not only reducing harm but potentially participating in energy transfer processes that make certain fungi unusually well-suited to persist where other life struggles. The deeper lesson is not that radiation is harmless, but that life’s repertoire of coping strategies is broader than our fear allows, and that an environment we name “dead” may simply be an environment whose living possibilities we have not learned to recognize.

Plastic as a New Food Chain

Plastic is a different kind of extremity, because it is not ancient like radiation or volcanic heat, and it is not a naturally recurring pressure that life has had eons to accommodate; it is, in a very real sense, an artifact of human intent, engineered for durability and then scattered at scale across oceans, soils, and cities.

For a long time, we treated plastics as “outside” biology, as though we had created a category of matter that would persist beyond the reach of living chemistry, and that assumption helped feed the bleakness that now surrounds the problem. Then research began to reveal a more complicated reality, including the discovery of bacteria such as Ideonella sakaiensis that can degrade and assimilate PET (polyethylene terephthalate), a common plastic used in bottles and textiles, using it as a significant carbon and energy source. This does not mean plastic pollution is solved, and it does not mean nature is quietly cleaning up after us at the pace we require, but it does mean the wall between “synthetic” and “biodegradable” is less absolute than our industrial mythology suggested.

The details matter, because the story is not magic; it is chemistry, step by step, and those steps are precisely why the discovery was so important. In the case of PET, I. sakaiensis uses enzymes often discussed as PETase and MHETase to break the polymer down into smaller components that can be taken up and metabolized, and subsequent work has investigated the structures and behaviors of these enzymes to understand how they bind substrates and how they might be modified for improved degradation. The significance, however, is not confined to one organism or one polymer, because the broader implication is evolutionary: when an abundant resource appears in the environment—even a resource we intended to be stubbornly inert—living systems will eventually explore ways to exploit it, not out of moral intention but out of ecological opportunity.

The danger is that we read this as permission, as though biology’s adaptive cleverness grants us moral credit, when the more honest reading is the opposite; if life is already beginning to metabolize our waste, it is because we have made our waste so pervasive that it has become, for some organisms, part of the new normal.

Organisms at the Thermometer’s Edges

If radiation and plastic feel dramatic because they intersect with human tragedy and human responsibility, temperature extremes remind us that life has always been an explorer of limits, long before we arrived with our technologies and our catastrophes. In the deep ocean, hydrothermal vent systems create conditions that appear almost designed to annihilate familiar biology, with high heat, crushing pressure, and chemical compositions that seem hostile to the cellular assumptions we carry from life on the surface.

Yet hyperthermophilic archaea demonstrate that the boiling point of water is not a universal stop sign, and organisms such as Pyrolobus fumarii have been described in the scientific literature as extending the upper temperature limits of life to around 113°C in certain contexts. That fact alone is startling, but it becomes even more instructive when you recognize that some hyperthermophiles are also adapted to high pressure environments, where pressure can influence molecular stability, and where life’s “operating conditions” are not merely about heat in isolation but about the full physical stack of constraints that define a niche.

The story becomes even more striking when you consider research around so-called “strain 121” (often referred to as Geogemma barossii strain 121 in the literature), which has been reported to reproduce at temperatures around 121°C under specific experimental conditions, thereby pushing the boundary of confirmed growth to temperatures associated with autoclave sterilization. Here again, the point is not that “sterilization doesn’t work,” because practical sterilization depends on time, conditions, and context, and because these organisms are not casually flourishing in your kitchen; the point is that life’s ceiling is not where we once assumed it must be, and that molecular repair, membrane integrity, and protein stability can be engineered by evolution in ways that feel almost like defiance.

When you move to the opposite end of the thermometer, the defiance changes form but not character, because psychrophilic organisms persist in environments where chemistry slows down, membranes stiffen, and ice threatens to tear cellular machinery apart. Studies on Arctic and marine psychrophiles such as Colwellia psychrerythraea show that these microbes can remain metabolically active after prolonged exposure to subzero temperatures (for example, around −10°C in ice), demonstrating that “frozen” is not synonymous with “dead,” and that life can tune its proteins, membranes, and stress responses to remain functional in conditions where our intuitions predict paralysis.

Taken together, the hot end and the cold end undo a comforting simplification, because they show that “extreme” is not a single condition but a family of conditions, each demanding its own biological architecture. Heat threatens unfolding and instability, so hyperthermophiles evolve stability, repair, and chemistry that treats boiling as background; cold threatens rigidity and slowed kinetics, so psychrophiles evolve flexibility, membrane strategies, and molecular systems that keep reactions moving when the world feels chemically quiet. In both cases, life does not merely endure the thermometer; it negotiates with it, and the terms of the negotiation are written into proteins, membranes, and metabolic pathways that look ordinary only if you forget how improbable they seemed before you learned they existed.

What These Thresholds Share

At first glance, fungi in radioactive ruins, bacteria learning to degrade PET, and microbes thriving beyond the boiling point of water sound like unrelated curiosities, as though nature were merely collecting strange anecdotes to impress a bored observer. Yet the connective tissue is simple and profound: life is not a static thing that either “works” or “fails,” but a dynamic process that searches for coherence between energy, matter, and replication, and that process continues as long as there is any workable pathway through the constraints. In that sense, resilience is not the refusal to be harmed, because harm is often unavoidable; resilience is the capacity to reorganize around harm, to turn stress into selection, and to make a living inside a world that does not promise comfort.

This is why our instincts mislead us, because we confuse our own fragility with the fragility of life itself, and we mistake our categories for nature’s laws. We call a place a dead zone, and then fungi appear that treat it as a niche; we call a polymer non-biodegradable, and then enzymes begin to appear that can loosen its bonds; we call a temperature “sterilizing,” and then somewhere in the deep ocean a cell maintains integrity and reproduces under conditions that rewrite our assumed ceiling. The lesson is not that nothing matters, or that nature will always recover, but that life is far more diverse in its strategies than the human imagination tends to be when it is trapped inside its own limits.

A Quiet Ethical Note

It is tempting to romanticize these stories as reassurance, as though biology’s ingenuity grants us a moral escape hatch, allowing us to believe that whatever we break will eventually be repaired by nature’s quiet intelligence. That temptation is understandable, especially in an era where ecological grief is easier to numb than to confront, but it is also dangerous, because “life persists” is not the same as “everything is okay.” Fungi surviving radiation do not undo human suffering or ecological damage; bacteria that degrade PET do not reverse the scale of plastic production and pollution; extremophiles thriving at thermal limits do not mean ecosystems are infinitely elastic under rapid climate disruption. Resilience describes possibility, not absolution, and it should invite humility rather than complacency.

If anything, these examples should sharpen our responsibility, because they show that the world responds to what we do, not with moral judgment, but with ecological rearrangement. When we flood the environment with new pressures and new materials, life will adapt where it can, but adaptation often comes with trade-offs, with losses elsewhere, and with novel ecological dynamics we may not like. Nature is not a courtroom, and it does not hand down verdicts, but it does keep accounts in the only currency it recognizes: survival, reproduction, and the shifting architecture of ecosystems over time.

If you want a single image to carry away from these thresholds, let it be the image of life not as a candle flame, but as a river that keeps finding channels, sometimes narrowing into cracks, sometimes widening into new basins, always moving toward some workable continuation. When you look at melanized fungi in irradiated rubble, at enzymes that can loosen the bonds of PET, and at microbes that treat boiling vents and subzero ice as ordinary neighborhoods, you are not seeing miracles so much as you are seeing the depth of the biological repertoire, and the sobering truth that “habitable” is a more fluid category than our instincts admit. Walk gently through the landscapes you inherit, speak clearly about the costs you externalize, and think bravely about the kinds of worlds your tools will leave behind.