The Illusion of Reality

The holographic principle sits at the pinnacle of physics as an amalgamation of the most outrageously unintuitive theories the subject has ever birthed; quantum mechanics, general relativity and thermodynamics, on this basis it deserves to be discussed with due diligence, this is my humble attempt to walk you through just that.

There is a quiet assumption we carry like a bone-deep habit: that reality is what it looks like. Space is a container. Time is a river. Objects are solid occupants moving through a three-dimensional stage, bumping into one another, leaving causes behind them like footprints. Even when we doubt other things—institutions, narratives, the motives of strangers—we rarely doubt the basic architecture of the world. Three dimensions. Forward time. Local events. A chain of consequences.

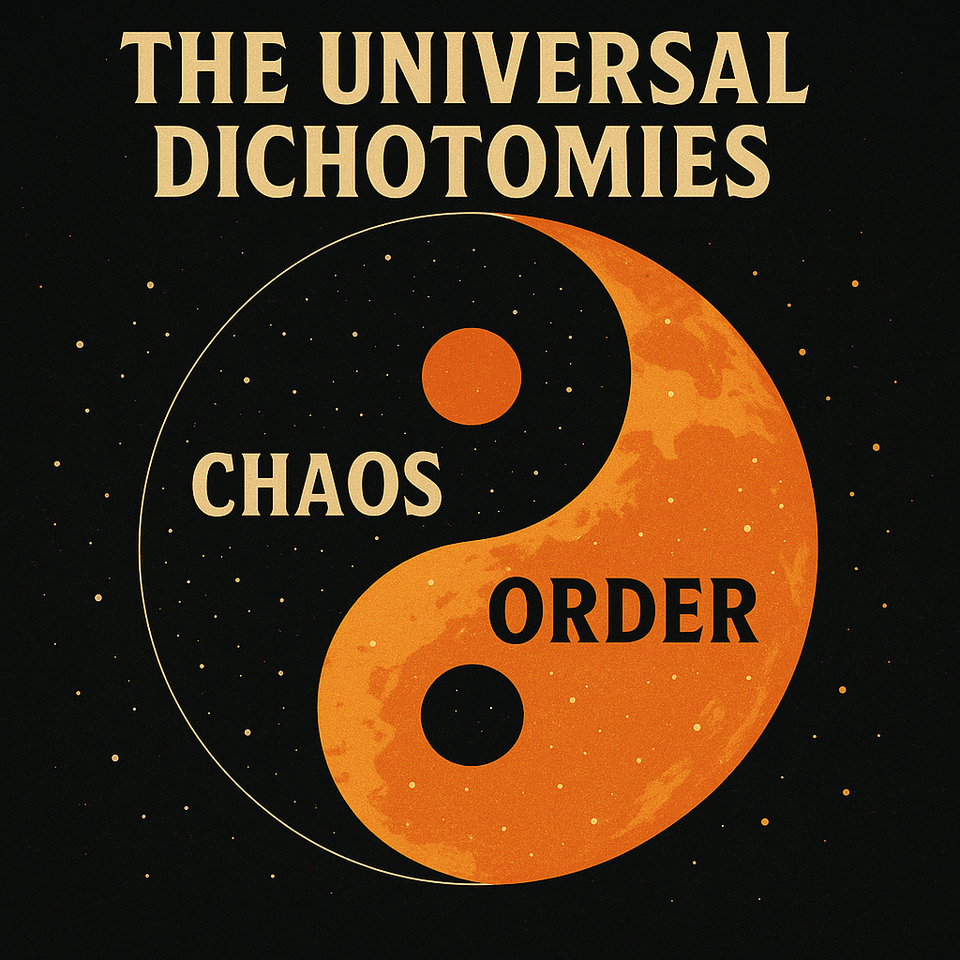

And yet physics has a way of humiliating our intuitions without mocking them. Again and again, the deepest descriptions of nature do not flatter the senses. The Earth is not still. “Solid” matter is mostly emptiness. The present is not universal. The world is not as it appears, but it remains real—only stranger, more layered, more reluctant to be reduced to the furniture of common sense. This essay sits in that tradition of discomfort, not as a stunt, but as a philosophical invitation: what if the three-dimensional world we inhabit is not the fundamental ledger of reality, but an emergent display of something more basic?

The holographic principle is one of the most unsettling hints we have that the universe may be built from information in a way our instincts do not anticipate. Not information as trivia, not information as gossip, but information as the difference between one state of the world and another—what makes this configuration distinct from all the alternatives it could have been. The principle suggests, in essence, that the deepest accounting of a region of space may be written not in its volume, but on its boundary; that what we call “inside” may be describable by what happens on the surface.

This is not an argument that the world is fake, nor an excuse to smuggle in the cliché of simulation. A hologram is not an illusion in the sense of being nothing; it is an image with depth that emerges from a surface description. The depth is experienced as depth. It behaves as depth. But its deepest encoding is not where you think it is. If the universe is holographic in this technical sense, then the illusion is not existence—it is our certainty about where existence resides, and how its bookkeeping is done.

To follow this thread, we have to approach a place where reality is forced to show its seams: the black hole. Not because black holes are mystical, but because they are brutally honest. They take the things we believe—about matter, time, entropy, and the conservation of what the universe refuses to forget—and they push them to the point of contradiction. If information cannot be destroyed, then a black hole cannot be a simple eraser. It must be, somehow, a recorder. And if the edge of a black hole behaves like a ledger, then the question naturally widens: what else might be written on the edges of things? What else might be encoded on horizons we mistake for mere borders?

What the Holographic Principle Actually Claims

The holographic principle begins as a sober statement about limits, not a dramatic claim about trickery. It says that the amount of information required to fully describe a region of space does not scale the way our instincts would expect. We imagine a room: double its width, height, and depth, and you have made more space for “stuff,” more capacity for complexity. Volume feels like the natural measure of how much reality can be packed inside reality. But the holographic principle suggests a different accounting, one that is almost offensive to common sense: the maximum information content of a region scales with the area of its boundary, not the volume of its interior.

This is easy to misunderstand, especially if you approach it with the wrong metaphors. It does not mean the universe is literally a flat screen. It does not mean your life is projected like a cartoon from a cosmic wall. It means something more precise and more unsettling: that the deepest description of what can exist “in there” is constrained by what can be written “on the edge.” The boundary is not a decorative outline. It is a limit, and possibly a language.

A useful way to hold the idea without sensationalism is to treat “information” as physics treats it: as distinguishability. If I say the system is in one state rather than another, I am making a claim that there are alternatives it could have been in, and that reality has selected one. Information measures how many such alternatives are possible, and how finely we could, in principle, differentiate between them. A world with no information would be a world with no difference—no texture, no identity, no separations worth naming. Information is not a human add-on. It is the skeleton of specificity.

Seen from that angle, the holographic principle becomes a claim about how specificity is bounded. It suggests that there is a maximum number of distinct physical configurations a region can host, and that this maximum is proportional to the region’s surface area. The interior may feel like the home of reality, but the ledger that counts reality’s possibilities seems to live on the boundary. Depth, then, begins to look like a phenomenon rather than a foundation: something that emerges from constraints, something that arises when information is organized in a certain way, rather than something that must exist as a primitive ingredient.

If you want a philosophical translation, it is this: what we experience as three-dimensional might be the way a deeper two-dimensional description appears from within. Not in the sense of deception, but in the sense of perspective. A hologram is not a lie; it is a transformation. The image has depth because the encoding, though surface-bound, carries relational structure that can be unfolded into a world. In the same way, the holographic principle hints that space itself may be an unfolding—an emergent geometry derived from informational relationships that do not require volume to be fundamental.

The principle, on its own, is a whisper. It tells us that boundaries matter, that surfaces are not mere skins draped over reality but might be the very place where reality’s bookkeeping is performed. To understand why such a strange claim was taken seriously by some of the sharpest minds in physics, we have to go to the most extreme boundary we know—one that is not made of material at all, but of causality itself. We have to go to the event horizon, where “inside” and “outside” stop being simple spatial categories and become epistemic ones.

Information as a Conserved Currency

Before black holes enter the story, we need to name the rule they threaten. Physics is, at its heart, an accounting discipline. It tells us what can change, what cannot, and what must remain invariant beneath the churn of appearances. We are familiar with conservation laws in the language of everyday intuition: energy does not appear from nothing; momentum is not conjured out of thin air. These are the rules that give reality its continuity, the quiet grammar that prevents the universe from becoming an arbitrary dream. But there is a subtler conservation principle that sits behind much of modern thought, and it is less comfortable to hold because it sounds almost metaphysical: the idea that information, in some fundamental sense, is not destroyed.

To say information is conserved is not to say that every detail is easy to recover, or that the universe is kind enough to hand us perfect records. It is to say something more structural: that reality does not permit absolute erasure. Changes may scramble. Processes may disperse. Complexity may hide what once was visible. But beneath that practical loss, the deeper description retains the difference between what happened and what could have happened instead. The world may be good at mixing, but not at forgetting. Even when the surface looks irreversible, the underlying bookkeeping remains, in principle, consistent.

This matters because so much of our lived experience is built on apparent one-wayness. We watch a glass shatter and we never see it leap back into coherence. We grow older, not younger. We remember, but we cannot un-remember. Entropy rises, and the arrow of time feels like a fact carved into the structure of the cosmos.

Yet much of fundamental physics, particularly the quantum story, is written as if the universe is reversible at its deepest layer. The basic equations do not select a preferred direction the way our experience does. The irreversibility we feel may be emergent, statistical, perspectival—real in practice, but not primary in principle. Conservation of information is part of that deeper posture: the insistence that beneath the apparent arrow, the universe is still keeping perfect accounts.

Philosophically, this is a profound claim. It suggests that reality has integrity, that what occurs is not merely a transient display but a transformation that preserves its trace. It is not that the universe is a moral witness, but that it is an ontological one. Something cannot be made to have never been by dropping it into the right kind of darkness. The past may be hidden, but not annulled. The world can conceal, but not annihilate.

And now we can see why black holes are not simply exotic objects. They are the universe’s most serious challenge to this conservation instinct. A black hole is a region where the usual paths of knowledge collapse. An event horizon forms, and with it a boundary that seems to sever inside from outside. Matter falls in, and from the perspective of the external world, it is gone—sealed behind a surface that offers no return, no report, no accessible detail. If black holes can also evaporate and vanish, as Hawking argued, then the temptation is terrifyingly simple: perhaps the universe really can forget. Perhaps there exists, in nature, a perfect eraser.

If that were true, it would not be a small correction. It would be a wound in the logic of physical law. It would mean that reality can leak coherence, that the ledger can be torn. And if that cannot be permitted—if information must be conserved—then black holes must be misunderstood. They cannot be mere sinks. They must be, in a deeper sense, archives. The question is where the archive is kept when the interior is inaccessible. The only place left is the boundary itself.

Black Holes as the Pressure Test for Conservation

A black hole is not simply a heavy object. It is an event in the logic of the universe: a place where our ordinary categories—inside and outside, before and after, knowable and unknowable—become strained. The defining feature is not the darkness, but the horizon. The event horizon is a boundary beyond which signals cannot return to an outside observer. Cross it, and whatever you are becomes causally disconnected from the rest of the cosmos, at least in the everyday sense of “connected.” The universe draws a line and says: from here onward, the usual routes of explanation are blocked.

This is why black holes become the sharpest test of whether reality truly conserves information. If something falls into a black hole, it seems to vanish from the accessible world. The external universe loses the details that made that thing distinctive. It is not merely that we cannot retrieve the information with current technology.

The horizon suggests a stronger claim: that the information is, in principle, sealed away from the outside, locked behind a boundary that does not negotiate. If the black hole then persists forever, you might say the information still exists, simply hidden. But Hawking’s insight complicates the picture. If black holes radiate and eventually evaporate, the entire object can disappear. The “container” that held the hidden information is gone. If the radiation that leaves carries no trace of what fell in, then information has not merely been hidden—it has been destroyed.

The tension here is not academic. It cuts to the heart of what it means for physics to be coherent. In the everyday world, loss of information is commonplace. A book burns, and the exact arrangement of ink becomes unrecoverable. A conversation fades into noise. A life ends, and the precise configuration of neurons dissolves into ash. But these are practical losses, not fundamental ones. The atoms persist. The energy is redistributed. The microscopic state evolves even if it becomes impossibly complicated to reverse.

If fundamental laws allow information to be destroyed, then reality gains a new permission: it can collapse distinct histories into the same outcome. Two different pasts can become indistinguishable in principle, not merely in practice. The universe would be allowed to forget the difference between what happened and what might have happened, and that is not a small loosening—it is a rupture in the idea that the world has a consistent ledger.

The event horizon is therefore not just a surface in space. It is a boundary in the epistemology of nature. It marks the point where “where did it go?” becomes a question that cannot be answered by looking harder. If the black hole evaporates and leaves behind radiation that seems featureless, then our ordinary notion of causality begins to wobble. Causes fall in. Effects leak out. But the link between them becomes opaque. A universe that conserves information must somehow preserve the link without letting us see it straightforwardly. A universe that does not conserve information must accept that the link can be severed.

This is the crucible that made black holes philosophically important. They are where the universe forces us to decide whether the deep rules are about appearance or integrity. Either information is conserved and black holes must encode what they swallow in a way that does not violate the horizon, or information is not conserved and the universe permits genuine ontological erasure. The first option preserves coherence but demands a radical rethinking of where information lives. The second option preserves intuition but undermines the very idea of a lawful, reversible substrate beneath the arrow of time.

It is here that entropy enters like a clue. Not entropy as a vague synonym for disorder, but entropy as a measure of how many microscopic realities can hide beneath the same macroscopic face. When Hawking studied black holes through this lens, he found something that feels like a message written in the geometry itself: the relevant counting does not happen in the volume. It happens on the surface. And once you see that, the horizon stops being merely a boundary you cannot cross. It becomes a page.

Hawking, Entropy, and the Hint Written on the Horizon

Entropy is the universe’s way of admitting that the world has more detail than we can hold in our hands. It measures, in essence, how many microscopic arrangements could correspond to the same outward appearance. A hot cup of tea looks simple, but beneath that simplicity is a swarm of molecular possibilities. Entropy counts the size of that hidden swarm. In this sense, entropy is not merely about disorder; it is about the number of ways reality can be, while still presenting the same face to an observer.

When Hawking turned this lens on black holes, something astonishing emerged. Black holes, which seemed at first like featureless voids defined only by a few macroscopic properties, behaved as if they carried entropy—an internal multiplicity, a hidden richness of possible microstates. That alone was provocative: if a black hole has entropy, it is not a simple object. It has a vast internal bookkeeping, a tremendous number of ways it could be “arranged” beneath its outward simplicity. But the more shocking part was how that entropy scaled. It did not grow with the volume you might imagine inside the horizon. It grew with the area of the horizon itself.

This is the first moment the holographic whisper becomes audible. The event horizon begins to look like more than a line in spacetime. It begins to look like the seat of accounting. If entropy measures the number of internal configurations, and if black hole entropy scales with surface area, then the number of possible internal realities of the black hole seems to be proportional to its boundary, not its interior. The horizon is behaving like a ledger. The surface is doing the counting.

Then Hawking introduced the twist that turned a strange result into a crisis. Black holes, he argued, are not perfectly black. Quantum effects near the horizon allow them to emit radiation. Over immense spans of time, they can lose mass and evaporate. This was not merely an add-on; it was a profound claim that black holes have a thermodynamic life. They have temperature. They radiate. They end. And if they end—if the black hole disappears—then whatever entered it cannot remain hidden inside forever, because “inside” no longer exists.

Here the paradox sharpens into a blade. If black hole radiation is purely thermal in the naive sense—random, featureless, indifferent to what fell in—then the evaporation process washes away the specific history of the black hole. A star, a library, a life could fall in, and the final output would not carry any signature of the difference. The universe would have found a way to collapse distinct pasts into the same outcome. Information would be destroyed.

That conclusion sits like a stone in the throat of physical law. It suggests that at the edge of a black hole, the universe behaves differently than everywhere else, permitting an exception to its own integrity. And yet the scaling of entropy is hinting at the opposite: that the black hole’s “capacity” to store information is written into the geometry of its horizon. The surface area behaves like a measure of how much can be recorded. The horizon looks, more and more, like a boundary that does not simply hide what crosses it, but registers it.

Philosophically, this is where the tone shifts. The event horizon is no longer merely a barrier to our knowledge. It becomes a kind of interface—between the world that can speak to us and the world that cannot, between what can be observed and what must be inferred. And on that interface, nature seems to have etched a rule: the deepest bookkeeping of what is swallowed is constrained by what can be written on the edge. The interior may be inaccessible, but the record may not be. The horizon may be silent, but it may not be blank.

If the universe refuses to forget, then whatever falls into a black hole must remain somewhere in the world’s ledger. Hawking showed us the scale of the ledger. The next step is to ask where the ledger lives, and what it means for a surface to carry the memory of a volume.

The Horizon as an Information Ledger

Once you accept that a black hole carries entropy proportional to the area of its horizon, the event horizon stops looking like a mere geometric boundary and begins to resemble an accounting surface. It is as though the universe is telling us, with a kind of austere indifference, that the “capacity” of the black hole is measured not by what it contains in some imagined interior, but by what its boundary can encode. The horizon becomes a page on which reality keeps track of what has crossed it, even if the interior remains inaccessible to us.

This is where it helps to be careful about language, because the mind reaches too quickly for literal images. An “information ledger” does not mean a glowing screen of symbols wrapped around a black hole. It does not mean we could, in principle, hover near the horizon and read off the biography of everything that fell in. The claim is subtler and, in some ways, more unsettling: that the deepest description of the black hole’s microstates—its hidden internal possibilities—can be counted as if they live on the boundary. The horizon behaves as though it is the place where the bookkeeping is done, even if the “meaning” of that bookkeeping is scrambled beyond recognition.

The phrase that often enters here is that information is stored on the horizon in a kind of “smeared” form. That is a useful intuition, as long as we remember that smearing is not erasure. It is transformation. If you throw a message into a fire and only capture the drifting ash and smoke, the original text is practically gone; but the universe has not violated conservation simply because your ability to reconstruct the message is lost. In the black hole story, the question is whether the horizon is the place where such transformation happens without rupture—where the distinctions that fell in are preserved, but rewritten into a form that no longer resembles the original objects. A ledger can keep accounts without keeping photographs.

From the outside, this becomes a peculiar inversion of what “inside” normally means. We tend to think that what is contained by a thing is held within it, that the interior is the true home of its content. But black holes, if information is conserved, suggest an alternate architecture: the interior may be where experience continues for the infalling observer, but the boundary is where the external universe’s accounting resides. The horizon becomes a kind of membrane between two descriptions, each valid within its own frame. What looks like “going in” from one perspective looks like “being written” from another.

This inversion carries a philosophical sting. It implies that our spatial intuitions may be narrations rather than foundations. We speak as if “where” is primary—where something is, where it goes, where it ends up. But the black hole pushes us toward a different primitive: not location, but information. Not “where did it go,” but “how is its distinctness preserved.” If the horizon is the ledger, then the fundamental question is not the fate of matter as substance but the fate of difference as record.

There is also a quiet implication about what a boundary really is. In ordinary life, boundaries are passive. A wall separates rooms, a skin separates body from world, a border separates nations. They are lines we draw and defend. The event horizon is different. It is not a material barrier; it is a causal one. It marks a limit of communication. And yet, paradoxically, it may be precisely such causal boundaries that do the deepest informational work. The horizon is defined by what cannot escape it, and in that very definition it becomes the surface on which the universe counts, constrains, and perhaps encodes.

If that is true, then the black hole is not a special case so much as a revelation. It is the place where the universe’s accounting becomes visible in the geometry itself. And once you have seen a boundary behave like a ledger, it becomes difficult not to ask the larger question. If information about an interior can be represented on a horizon, what else might be representable in this way? If a region of spacetime can be “described” by its boundary, is this a trick reserved for black holes—or a principle whispered by them?

That widening of the question is where Susskind enters the story, not with a single dramatic leap, but with a willingness to take the horizon seriously as more than a local curiosity. If the boundary can encode the bulk, perhaps the universe has been holographic all along, and black holes are simply where the hologram becomes impossible to ignore.

Susskind’s Expansion: From Black Holes to the Universe

Once the horizon begins to look like a ledger, the temptation is no longer to treat it as a clever hack of black hole physics, but as a clue about reality’s general architecture. Leonard Susskind’s contribution was to lean into the implication that black holes were not merely pathological objects at the edge of theory, but revealing ones. If a region of space could be fully accounted for by information residing on its boundary, then perhaps boundaries are not just where reality ends, but where reality is written. The black hole horizon would not be an exception. It would be a signature.

This is the point where the phrase “holographic principle” earns its name. A hologram stores a three-dimensional image in a two-dimensional medium, and the depth we perceive is a kind of unfolding of relational information. Susskind’s expansion takes that intuition and makes it cosmic. If the deepest accounting of what happens in a volume can be represented by a surface, then the three-dimensional world might be an emergent interpretation of a more fundamental two-dimensional description. Not a deception, not a theatrical trick, but a fact about compression and encoding: the bulk might be, in some deep sense, redundant.

It is important to keep the discipline of what is being claimed here. The idea is not that the universe is literally a projection in the cinematic sense, as if some exterior observer is shining light through a stencil. The idea is that physical reality may admit two equivalent descriptions: one that speaks in the language of a volumetric interior, and one that speaks in the language of a boundary. If both descriptions can capture the same truth, then “space as volume” becomes less like a fundamental ingredient and more like a perspective-dependent narrative the universe allows. We do not have to say the world is unreal to say it might be representable in a way that does not privilege depth.

In this framing, the event horizon is not just a border around a black hole. It becomes a prototype for horizons more broadly, and horizons show up in more places than we first notice. They appear wherever there are limits to observation, limits to access, limits to what information can be gathered from within a region. A horizon is a boundary defined not by material walls but by the structure of causality and spacetime itself. If such boundaries are where the maximal information content is registered, then the cosmos is threaded with surfaces that matter.

Susskind’s enlargement of the idea therefore does something psychologically radical. It shifts our sense of what is “primary.” We are trained to think of the surface as a skin draped over a more substantial interior. But if the surface carries the full accounting, then the interior begins to look like the experienced manifestation of constraints written elsewhere. The inside is not dismissed, but reinterpreted: it is what the boundary-description looks like from within. Depth becomes the way information feels when it is unfolded into geometry and lived through as distance.

This is where the philosophical temperature rises, because the notion begins to touch everything. If the universe as a whole has a kind of boundary description, then the totality of what can occur in the cosmic interior would be constrained by what can be encoded on that cosmic edge. The world we walk through, the sky we measure, the time we inhabit, would all be emergent expressions of informational limits. Reality would not be “made of” space in the ordinary sense. Space would be what reality looks like when information is arranged in a certain way.

You can hear, at this point, why the title “The Illusion of Reality” becomes more than a provocation. The illusion is not that there is nothing there. The illusion is that what is there must be volumetric in the way it presents itself. The holographic principle invites a reversal: perhaps the world is not a container filled with things, but a coherent pattern whose deepest description is written on the edges of what can be known.

But to take that seriously, we have to confront what it means for depth to be emergent rather than fundamental. If the bulk is a kind of unfolding, then our most basic intuitions about “here,” “there,” and “between” begin to look like interface-level concepts. And once you consider that possibility, the next question becomes unavoidable. If space can be emergent, what else might be?

Emergence: When Depth and “Here” Are Not Fundamental

There is a difference between something being unreal and something being emergent. A rainbow is emergent. It is not a material object you can pick up and carry home, but it is not a hallucination either. It is a real phenomenon that arises when light, water droplets, and perspective align in a particular way. Temperature is emergent. It is not a property of any single molecule, yet it is meaningful, measurable, and decisive for the behaviour of matter. Emergence is the universe’s way of building higher-level realities from deeper rules, allowing new concepts to be true without being fundamental.

If the holographic principle is pointing in the direction it seems to point, then space—at least space as we intuitively imagine it—may belong in that category. The depth we experience, the sense of an interior distinct from a surface, the feeling that “here” is a coordinate inside an enormous container, could be an emergent description rather than a primitive fact. Space would remain real in the way temperature is real: not an illusion in the dismissive sense, but a macroscopic language that holds reliably within its domain. The shock is not that space fails, but that it may not be the bedrock we assumed it to be.

This reframing changes the meaning of boundaries. In ordinary thinking, a boundary is drawn inside a pre-existing space. The room exists first; the wall divides it. The body exists first; the skin encloses it. But if space itself is an emergent unfolding of information, then boundaries are not merely partitions inside space. They may be part of the machinery that gives space its very shape. The holographic principle suggests that the boundary can carry the full informational capacity of the interior, which implies that the interior’s reality is, in a sense, overdetermined by what the boundary can encode. The “bulk” becomes a kind of readable consequence of a surface constraint.

There is a gentle way to hold this without sliding into cheap metaphysics. The point is not that the universe is secretly two-dimensional and we have been duped. The point is that the universe may permit descriptions that do not line up with our sensory hierarchy. We privilege volume because we live in it. We privilege locality because our bodies are local. We privilege “inside” because our minds have boundaries and our lives have skins. But physics has no obligation to honour those preferences. It only has an obligation to be consistent with itself.

If space is emergent, then distance becomes less like an intrinsic separation and more like an informational relationship. “Far” and “near” would not be primary facts but derived ones, expressing how tightly coupled two sets of information are within the deeper description. The world would still present itself as geometry, because geometry is the language by which such relationships become navigable from within. But the geometry would not be the source. It would be the interface.

This is where the title begins to sharpen. The illusion is not that reality does not exist, but that reality must be structured the way it appears from the inside. We assume that the inside is the fundamental place where things happen and the surface is merely the outline. The holographic principle suggests the opposite emphasis: the surface may be where the accounting is complete, and the inside may be the lived interpretation of that accounting. The world remains, but our hierarchy flips.

And yet, if we accept even the possibility of this reversal, a more intimate question starts to press in. Our experience of space is bound up with our experience of time. Our sense of “here” is braided with our sense of “now.” And our sense of “now” is braided with causality—with the feeling that events produce events, that the world unfolds as a chain rather than a block. If the interior is an emergent unfolding of a boundary description, then the next question is not merely where things are stored, but how they happen at all.

To get there, we have to name the illusion explicitly, not as a claim that the world is false, but as a claim that appearance is not the final judge of essence. We have to look at what “reality” means when it is understood as a layered description rather than a single face.

The Illusion of Reality

When people hear the word illusion, they often hear an accusation: that what you are experiencing is not real, that you have been fooled, that the ground beneath you is made of smoke. That is not what this is. The illusion suggested by the holographic principle is subtler and more existential. It is the illusion that the way reality presents itself to us is the way reality is constructed at its deepest level. It is the quiet assumption that the universe must be made out of the same kinds of things our senses can comfortably picture: volumes filled with objects, distances separating bodies, moments marching forward like beads on a string.

But the story we have been tracing hints at a layered world. There is the reality we inhabit as lived experience, and there is the reality described by the most stringent forms of accounting we have. These are not two different universes. They are two different descriptions of the same universe, held at different depths. The experienced layer is made of surfaces and depths, of here and there, of before and after. It is the stage upon which life is possible, the domain where choice has meaning because events arrive in sequence and actions have consequences in time. It is real because it is the domain in which we are real.

And then there is the descriptive layer that keeps refusing to respect our intuitions about where the “real” must reside. In that layer, boundaries do the counting. Horizons behave like ledgers. The maximal information content of a region seems to scale with its surface area, as if reality’s capacity is tied to edges, not interiors. The world, in that description, begins to look less like a warehouse and more like a script: not because it is predetermined in the crude sense, but because it is structured by constraints that do not require volume to be fundamental. The three-dimensional interior feels like the primary fact, yet the bookkeeping suggests the boundary is enough.

If you let this sink in, the illusion is revealed as a kind of perceptual arrogance. We assume that because we live inside the world, the inside must be the deepest layer. We assume that because we move through space, space must be a primitive container. We assume that because the present feels sharp and singular, time must be an objective flow. These assumptions are not stupid; they are adaptive. They are the forms of intuition that make survival and meaning possible. But adaptation is not the same as metaphysics. A mind shaped to navigate a world does not automatically possess a mind shaped to describe the world’s foundation.

This is where the theatre metaphor becomes more than decoration. Reality may be the stage, but the stage is not the script. The stage is what the script looks like when it is performed from within. If the holographic principle is even partly right, then what we call “depth” is a kind of performance—an emergent phenomenon produced by a deeper informational structure. The illusion is believing that the performance exhausts the play, that the surface show is the full mechanism.

And yet, even this must be held with humility. A hologram does not negate the image; it produces it. The experienced world does not become irrelevant because a boundary description might underwrite it. If anything, the opposite happens: the experienced world becomes more precious because it is the rare place where abstract constraints become lived texture. The illusion is not that life is meaningless. It is that the only meaningful layer is the one we can picture.

From here, the final question is unavoidable, and it is the one that reaches most directly into our lives. If the deepest accounting of a region is bound to its surface, and if the universe itself might admit a boundary description, then what does that imply about time and causality? We have treated causality as if it is the engine of reality, the rule that makes the world intelligible: action preceding consequence, the arrow of time, the unfolding of events. But if everything that can happen is constrained—or in some sense encoded—by a boundary ledger that does not share our inside perspective, then causality begins to look less like the universe’s foundation and more like the universe’s interface.

If the Record Is “Already Written,” What Happens to Causality?

Causality is the most convincing story reality tells. It is so convincing that we rarely recognize it as a story at all. We experience the world as sequence: a thought, an action, a consequence; a spark, a flame, a rising heat; a word, a wound, a silence. Cause precedes effect. Time moves forward. The past is fixed, the future open. This is not merely a belief—it is the architecture of lived life. It is how the mind keeps the world coherent and how the body survives within it.

But the holographic principle, taken seriously as a philosophical provocation, invites an unsettling reversal. If the deepest description of a region can be written on its boundary, and if black holes forced us to imagine horizons as ledgers where information is conserved rather than erased, then the universe begins to look like a kind of total record—an accounting that does not necessarily privilege our sense of “before” and “after.” This does not mean the future is fated in the crude sense, or that choice is theatre with no stakes. It means something stranger: that the universe might be describable as a whole, and that our experience of unfolding might be the way that whole is read from within.

One way to hold this is to imagine that time is not the author, but the reader. The boundary description, if it exists, would be less like a prophecy and more like a completed structure—an informational constraint that contains, in principle, the distinctions between all possible histories the universe could realize. From within the interior, those constraints are lived as dynamics. We do not experience “the whole” as a static object. We experience it as motion, as process, as becoming. Causality, in this lens, is what constraint feels like when you are embedded inside it.

Another way to hold it is even more modest, and perhaps more honest. The boundary record need not be a frozen script of events. It could be a rule-set rather than a timeline, a set of informational limits that shape what can occur without specifying a single predetermined story. In that reading, the ledger does not tell you what will happen; it tells you what is permissible. It defines the space of possible unfoldings, and the interior world is the arena where those possibilities become particular. Causality remains meaningful, but it becomes contextual: it is the local grammar of how the interior realizes what the boundary allows.

And there is a third way, the one that most cleanly preserves both wonder and humility. Perhaps causality is not fundamental. Perhaps it is emergent—real where we live, indispensable for beings like us, but derivative in the deeper description. We already accept this with other concepts without feeling threatened. We accept that solidity is emergent, that the table is mostly empty space, yet we still place our cup on it. We accept that temperature is emergent, yet we still feel the burn. Causality could be similar: a reliable macroscopic interface that arises when information is arranged in certain stable patterns, not the deepest engine turning beneath everything.

If that is true, then the most unsettling possibility is not fatalism. It is reframing. It is the idea that “cause and effect” may be the way consciousness navigates an informational world, not the way the informational world is fundamentally stitched together. The arrow of time, so intimate to our lives, could be the shadow of deeper constraints rather than a primary beam. The chain we call causality might be the narrative form of conservation: the universe cannot forget, so the world must remain coherent, and coherence—experienced from within—arrives as sequence.

This is where the title becomes less dramatic and more precise. The illusion is not reality. The illusion is our certainty that the deepest layer of reality must resemble our experience of it. We insist on a volumetric universe because we live in volume. We insist on a flowing time because we live in flow. We insist on causality as bedrock because we are creatures who must act, and action requires a before and an after. But the holographic principle suggests that the deepest accounting may be written at the edges, and that the interior—our interior—may be an emergent reading of that edge.

If everything that could ever be or has ever been is, in some sense, conserved as information, then the universe is not a stream that forgets its own source. It is a ledger that transforms without erasing. And if that ledger can be represented on a boundary, then perhaps the interior is not where reality is stored, but where reality is performed.

Perhaps causality is not the engine of the universe. Perhaps it is the way a mind reads what cannot be lost.